Anyone who has ever been to a Tibetan Buddhist temple or a California meditation center has probably seen the Bhavachakra. Known in English as the Wheel of Life, the Wheel of Becoming, or the Wheel of Suffering, this popular mandala depicts the structure and dynamics of samsara, the universe of cyclic existence. As with other traditional Buddhist images, the Bhavachakra is loaded with stylized figures and arcane symbols, each rendered in strict accordance with long-established formulae regarding placement, color, size, bodily proportion, etc. Not surprisingly, Buddhist art is not about self-expression; rather, it is meant to facilitate spiritual awakening.

When I first encountered this fact, and Buddhist iconographic painting in general, I was fascinated and perplexed. I had just arrived for a multi-month stay at Norbulingka, an institute in northern India dedicated to preserving Tibetan art and culture. Although my position as volunteer graphic designer ostensibly involved sitting in front of a computer, I would often wander into the painting studio to watch the young trainees working diligently on their thangkas. I was impressed by their deep concentration, captivated by their beautiful handiwork, and hard pressed to define what I was seeing. Was it art or craft? Were these Tibetan refugees to be admired as exemplars of selflessness or pitied as paintbrush-pushing peons?

I was, after all, raised in the US, where art is primarily a secular thing, a commodity even, and where being an artist—a real artist, anyway—involves trashing tradition and forging a unique pathway to infamy. A Bohemian by blood, I had adopted the label of “artist” after learning to draw Snoopy in kindergarten, and later adopted Salvador Dali as my personal hero, partly because of his utterly bizarre persona. I took tons of art classes in college, majored in graphic design, and subsequently pursued my childhood dream of being a cartoonist, albeit more Tom Tomorrow than Charles Schulz.

Then, during my stay in India, I got into Buddhism. My affections changed from Dali to the Dalai Lama, whom I met several times at Norbulingka, one of many institutions over which he technically presided. In fact, my living quarters were located just below the sweet suite reserved for His Holiness’ occasional visits. And just outside my front door, adorning one wall of the ornate, brightly colored central temple, was a magnificent rendering of the Bhavachakra. Every day on my way to “work,” I would pause to marvel at the intricacies of the cosmos within which I was presumably embedded.

A Brief Breakdown of the Universe

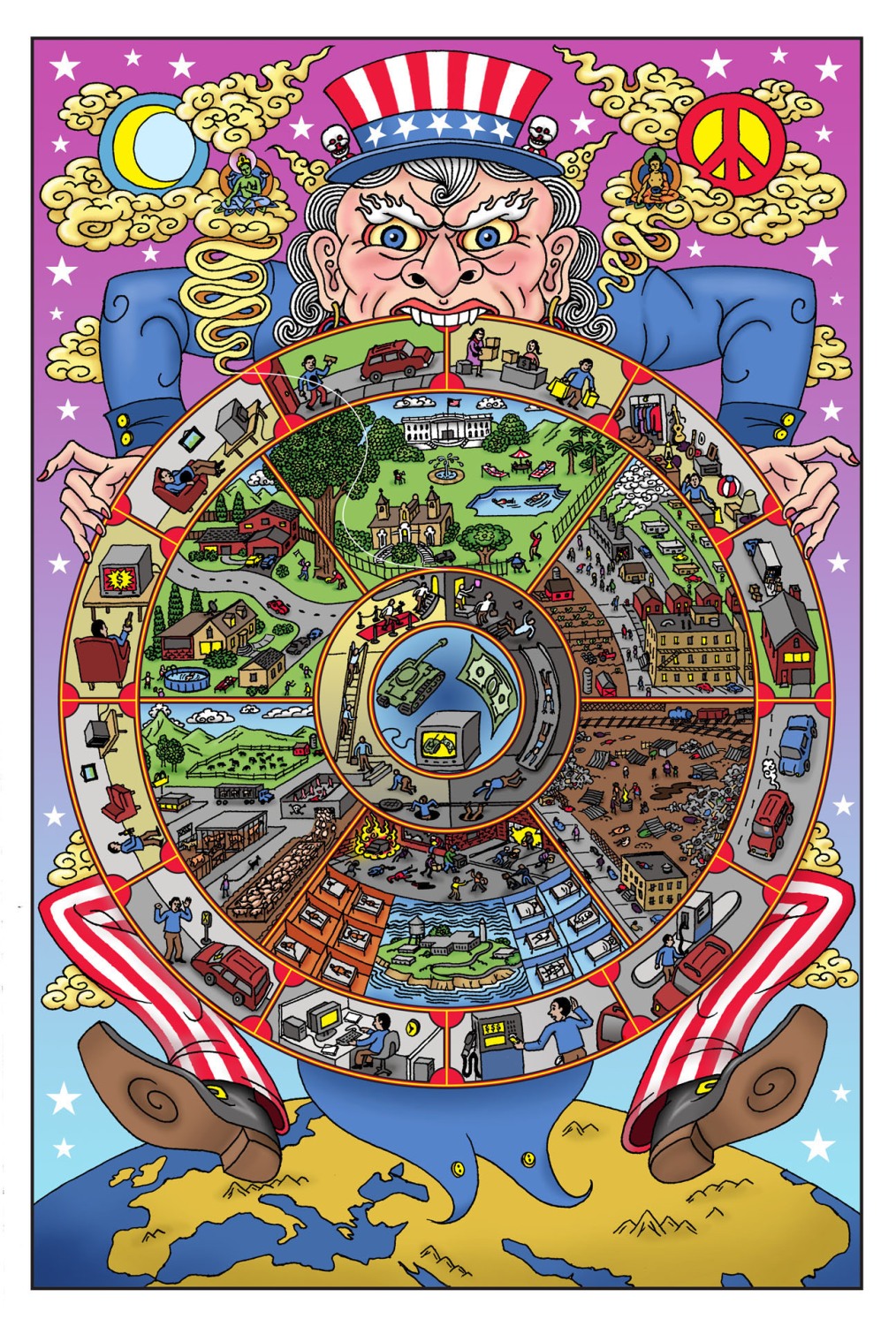

Having returned full circle to the Wheel of Life, I now present the basic layout, from the inside out. Smack in the center of the wheel there appear a rooster, snake, and pig, representing desire, aversion, and ignorance (the three poisons or root causes of suffering). Just outside this inner circle is the ring of karma, within which tiny figures rise on one side and descend on the other. The main part of the wheel is divided into six pie slices depicting the six realms of existence (those of the gods, demigods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts, and hell beings), while on the outer rim are depicted the twelve links of dependent origination (which I won’t get into here). The whole of the wheel is held in the grip of Mara, the demon of illusion. A moon in the upper left corner symbolizes liberation, while the Buddha in the upper right points the way.

As complicated as this all might sound, the Wheel of Life is often used as a teaching tool for children, containing as it does many core concepts of Buddhism. The image is designed to provide the viewer with a quick download of dharma and, ideally, inspiration. For despite Mara’s menacing features and the system of suffering over which he presides, his main function is to remind us that nothing is permanent. Neither hell beings nor even gods dwell eternally in their respective realms, but are reborn elsewhere in accordance with their karma. And all beings have Buddha nature, the capacity for full awakening. Essentially the Bhavachakra, like Buddhism in general, is primarily about freedom.

A Sort of Homecoming

So too does the USA stand for freedom, or so I had been taught. When I finally returned stateside after over a year in the shadows of Shangri-La, my reverse culture shock was profound. Although I had seriously considered staying indefinitely in India to study Buddhism and perhaps even become a monk, I realized almost immediately why my conscience had called me back. Where once I had perceived only sickening abundance, I now saw abundant sickness and heard a desperate cry for help. My former cynicism had (mostly) morphed into compassion. I had, in effect, been reborn into the realm of my own culture, and into a full awareness of the ubiquity of suffering. It’s no less present in the McMansions of the Midwest, I grokked, than in the hovels of Himachal Pradesh.

In fact, the America of my rebirth seemed even more mired in misery than any so-called “developing country” I had ever visited. I saw it in the ostentatious affluence, the pervasive obesity, and the vacant expressions of my fellow countrypersons. It was apparent in the advertising that relentlessly assaulted the senses and insulted the intelligence. And it was there in the statistics: epidemic use and abuse of prescription drugs and painkillers, world-record rates of violent crime and incarceration, widespread heart disease and other stress-related illness, chronic over-consumption habits leading 5% of the planet’s population to ravage 1/3 of its resources, and a military budget as big as the rest of the world combined. To my acclimating eyes, the pursuit of happiness appeared to be an epic failure.

As for freedom, I could only recall Goethe’s observation that “none are more enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.” As I settled back into American life, I had the unsettling realization that the whole country was little more than an elaborate prison in which the inmates were also wardens, and the walls made of illusions maintained by an invisible entity I came to call “Uncle Samsara.” Indeed, the more I thought about American culture, the more it seemed like an extreme caricature of the human condition as depicted in the Wheel of Suffering. The cartoonist in me couldn’t resist flushing out the parallels, although it wasn’t until years later that I committed the scheme to paper. It is now preserved for posterity as a freely downloadable, tabloid-sized, digital image whose title matches that of this article. Like all cartoons, it embodies a certain amount of snark, but like the Bhavachakra, its ultimate purpose is to educate and to inspire genuine freedom.

A Key to the Matrix

What follows is a description of my mandala, again from the inside out. At the hub of the wheel appear a dollar bill, a tank, and a television, representing the three poisons of greed, hatred, and delusion (these exist institutionally as materialism, militarism, and the media). Just outside the central circle is the ring of financial karma, in which people slowly climb the ladder to prosperity, only to slide back down into a hole of debt.

The main part of the mandala depicts the Six Realms of Socioeconomic Existence. At the top is the Imperial Realm, in which ultra-wealthy beings live in mansions, ride in limousines, and suffer from arrogance, isolation, and the occasional bad hair day. Below and to the left of this realm is that of the Imperial Wannabes, who abide in sprawling suburban homes, drive expensive cars, and suffer from envy and existential angst. To the right of this realm is the Public Domain, populated by working class humans who live in modest homes, apartments, and trailers, and drive used cars. They speak highly of freedom while being severely constrained by desire, fixation, and fear. Many of them suffer from high blood pressure, low self-esteem, and bad credit. Lower on the ladder lies the Animal Turf, wherein many creatures are subject to displacement, confinement, and cruelty on the part of humans. Some of them are kept as pets and often treated much better than beings in the adjacent Homeless Dimension. This realm is populated by nearly invisible “hungry ghosts” who wander endlessly in search of food and shelter. The lowest of all realms is the Hellish ‘Hood, the residents of which suffer from intense anger and psychological illness. Beings in this realm possess very little freedom, whether held captive in prisons, mental institutions, or army barracks.

The outer wheel depicts the Twelve Steps of Codependent Consumerism. The sequence begins and ends with shopping, an activity which leads directly to the accumulation of material objects. Possessing lots of stuff leads to the need for a “stuff storage facility,” commonly called a house and usually located outside of town. This necessitates having a motorized vehicle with which to transport one’s person, groceries, and additional stuff. Driving a car necessitates buying gas, which contributes to debt and the need to maintain employment. Working generates stress, which leads to an urgent desire for relaxation. This often involves consuming alcohol and/or watching television. Depressants, TV and advertising all contribute to a sense of lack or emptiness, symbolized here by a black hole. This feeling of worthlessness leads to an impulse to shop, which begins the cycle anew.

The Wheel of Suffering is held in the clutches of the aforementioned Uncle Samsara, the Lord of Illusion. This fearsome figure presides over a vast empire of desire, despair, death and taxes. Outside of this wheel lies liberty in the form of planetary consciousness, lunar consciousness, and compassion (symbolized by a green Tara). Ultimate freedom is found in the form of cosmic consciousness, wisdom and peace (symbolized by a meditating Buddha).

May all Americans, and all beings everywhere, be happy and truly free.

Love your writing and artwork!!

This is very cool! Love it!

read all about it on reality sandwich. Love it, clever and intelligent. And very very truthful. As a disaffected, formerly homeless, American, you really pinned it down. Thanks!

Fantastic!

Personally, whatever the subject, I find this text difficult to read. Hate to squint when I’m trying to absorb.

I read many articles here and appreciate it; thanks for sharing with us. Also, I noticed Tibetan Mandalas all show a Buddha somewhere in each realm. I do not see that in your Mandala and think it would make a great addition to maintain that teaching. I also, just shared your Mandala with a friend of mine who is now very interested in your work as well. We hope you keep sharing here. Thanks.

-Joe

Fantastic and inspiring. Thank you.